|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Essay by Ranald MacInnes. Historic Scotland. May 2003

Dalquharran Castle was designed and built in a landscape setting from 1781 for Thomas Kennedy Esq. of Dunure, a distant relative of the Kennedy family of Cassilis and a descendant of Thomas Kennedy of Kirkhill, Lord Provost of Edinburgh, who bought the estate in the late 17th Century. The client's wife, Jean Adam, daughter of John Adam, was Robert Adam's niece. Adam created a moderately sized building for the couple but in the 1880s the Baronial Revival specialists Wardrop and Reid added two large wings in a sympathetic style. As a result, some of the compact, pavilion-like glamour of the composition was lost. The added wings had made a relatively small house quite grandiose. After many years of continuing difficulties, during which the house was used, underused and finally abused, in common with many of our larger country houses, Dalquharran fell into terminal; decline in the 20th Century and was finally un-roofed to avoid paying rates in 1968.

Dalquharran and the Castle Style

However, we must remember that for the 18th Century, symmetry was an almost sacred architectural convention (illustration Barnbougle) This situation would not substantially change until well into the 19th Century with a renewed interest in 'organic' architecture: intuitive or 'natural' design. It is largely through Adam's many drawings of castles in mountain settings that we can appreciate the sources of his desire to create romantic buildings in 'designed' landscapes.

A new interest in 'natural' landscapes had begun to develop in the middle of the eighteenth century. This would finally transform into a full blown romantic movement with Sir Walter Scott leading the tourist influx to the Highlands but the first response of Adam to this movement was to paint and draw romantic castles in a wild setting. It is clear from looking at perspective views of Adam's castle, including Dalquharran, that the architect's inspiration lay in the landscape: the idea of a complete scene. (illustration of Adam's view of Dalquharran) .

Then, from around 1770, beginning at Wedderburn, Adam began to design new country houses in the form of 'castles'. This was an extraordinary thing to do, even if the most obvious and recent precedent for castellated designs was Inveraray which had been designed in the 1740s (illustration).

However Inveraray was essentially a different type of castle. It belonged to an earlier, much more superficial revival of interest in Gothic architecture. William and John Adam were the 'job' architects for Inveraray and and the Adams also designed their own, cut-down and only half completed version at Douglas Castle in Lanarkshire, later illustrated in the collection of William Adam's work, Vitruvius Scoticus. However, another, more direct, influence on the later Castle Style of Robert Adam was that of the castellated palaces and houses of the Scottish Renaissance, which tended to symmetry. Adam himself drew the James V tower at Holyrood Palace with Arthur's Seat in the background, so clearly this was a source. This interest in the actual buildings of the Scottish past, is what took Robert Adam's castles to a far higher architectural level. Adam had worked at a key Scottish building of the earlier 'revival' of interest in the past, Thirlstane, and he came close to the much later concern with accurate 'recording' of the Baronial at Cluny in Aberdeenshire. There was also, from the beginning, a considerable overlap between Adam's castles and elements of his classical house architecture, including not only the general principle of symmetry and classical interiors but also more specific external features of the classical houses: for example, the massive twin-tower gateway on the south front of Luton Park. The castellated house designs built by Robert (and James) Adam fell into two phases. The first was a group of relatively plain, rectangular houses. These projects included Mellerstain, c.1770-8 (a new block, with refined classical interiors, built to link existing wings); the bow-fronted, turreted Wedderburn (1771-5) (illustration) and the plainer Caldwell (1773-4).

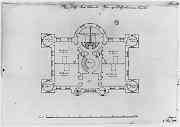

However, from the mid 1770s, Adam started a series of much more romantic compositions. These exploited the play of light and shade, with the boldly geometrical shapes of towers and turrets. This second group began with an unbuilt scheme of 1774 for the 3rd Earl of Rosebery, which proposed the transformation of the 'L' shaped tower-house of Barnbougle Castle into a splay-planned block with bastion-like courtyard. Although the Castle style designs form an instantly recogniseable group, there was always an overlap with Adam's ecclesiastical designs. In these turreted, triangular forms, there was a strong similarity with classical house design, including both his father's Minto and the neo-classical geometry of his own Walkinshaw (1792): this late design was the closest Adam came to designing a hybrid castle-classical house. An earlier splay-plan castellated design, also unexecuted, was that for Beauly Castle (1777). Castles which were actually built in this manner included Culzean (from 1777; north elevation from 1785); Oxenfoord (1780-2); Dalquharran (from 1782, and extended 1880 to its present length); Pitfour (c.1785); Seton (1790), which echoed the rippling attached towers of Bruce's Thirlstane; Airthrey (from 1790); and Stobs (1792-3). In all these cases, severe, tower-like blocks with unadorned neo-classical fenestration were arranged in symmetrical clusters and plan-forms which were designed to be suitable for axial views, but, at the same time, to 'read' asymmetrically when seen in landscape. Another significant unexecuted castellated design was that for Fullarton (1790) where only the stables were built and survive converted to housing. However it was at the 'whimsical but magnificent Castle of Colane' (in the words of Clerk of Penicuik, in 1788), that Adam's patron, the 10th Earl of Cassilis, a lawyer and MP, encouraged the architect to 'indulge to the utmost his romantic genius'.

Adam added to Culzean, already enlarged in 1777, a new block

containing a circular saloon, library and bedroom suite, and hollowed

out an elliptical staircase inside the original section. The house

was reached by a new landscaped approach across the designed 'ruin'

of a causeway. Much of what was realised at Culzean, Adam's finest

castle composition, had been worked out at Dalquharran, particularly

of course the great round tower but also the completeness of the

setting, the totality of buildings and landscape Notes and References 1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||