Free Gardeners Home | Diversity | Edinburgh

The Society of Gardeners in and about Dunfermline

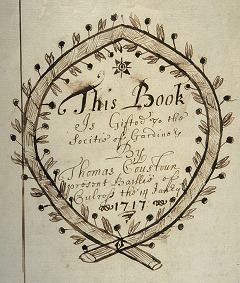

The society was founded in 1716. Like many early gardeners' associations, it may have grown out of an earlier body. It used a variety of names over the years. It is often recorded as the Dunfermline Gardeners' Society or, more formally, the Ancient Society of Gardeners in and about Dunfermline.

The Gardeners were not numbered among Dunfermline's incorporations and trades guilds. Hence their status was at first sight lesser. In partial compensation, their rules were more flexible. That the society could not be an incorporation in law does not appear to have bothered the founders unduly as their 'bond of union' follows almost exactly the form of an incorporation's seal of cause and they refer to themselves throughout as both a fraternity and an incorporation. The senior officers were at first a Deacon and a number of masters, also just like incorporations. Later, the most senior position was titled 'Chancellor', which is believed to reflect the growing influence of non-operative members.

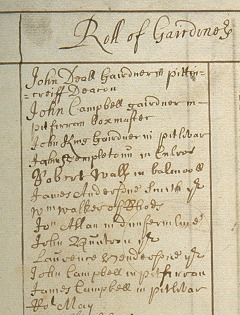

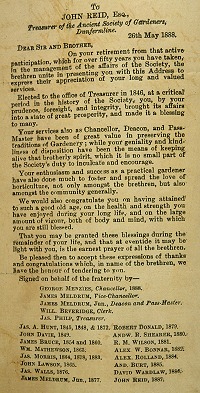

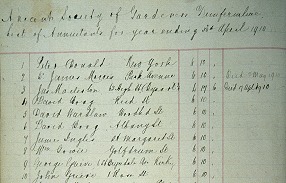

The society was popular from the outset. From the first local 'gentry' enlisted in some numbers, although they paid different rates than practicing gardeners. This essentially gave the society a cachet or social position that was unavailable to the town's incorporations, which were restricted solely to craftsmen. Other professionals - lawyers, military men, ministers and doctors - also joined the Gardeners. In a history published at the society's centenary a complete membership list was printed. It emphasised the titled and professional men, who were headed by a duke, a marquis, 6 earls, 7 lords, 8 knights and hundreds of professionals (soldiers, ministers, advocates) and other landowners or lairds. The list appeared regularly, with additions, during the society's second century. Interestingly, upper class interest was at its greatest during the first fifty years of the society; few notable additions were made to the first published list. By the end of the eighteenth century such illustrious company had faded away except for a leavening of Dunfermline based professionals.

The Society was able to invest surplus cash in land. It purchased a substantial plot just outside the then boundaries of the burgh of Dunfermline in the first half of the eighteenth century. Business minutes record in detail expenditure relating to the administration of the property and the subsequent revenue that the society earned from it. Although at first some of the land was let in the short term, providing rental income, the society's sustained wealth was secured by selling feus on the land. Each feu provided both a once and only lump sum in cash and a continuing feu duty, which was still being levied into the 1990s.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the rules of society were emended to enhance its role in providing sickness, funeral and widows' benefits; to some extent the original gardening objectives were neglected. However, for many years a horticultural fund was maintained with a programme of exhibitions and prizes. In the nineteenth century this was reformulated as a separate 'Horticultural Section' with separate membership terms and dues - a small annual fee to cover administration of the events and prizes.

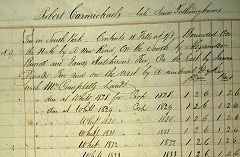

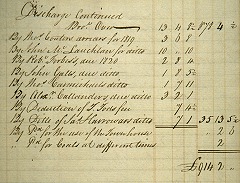

By 1828 the society had feued fifty individual plots on its land. They received in return annual sums ranging from 17/6 (87.5p) to £9.17.6 (£9.875), around £80 in total. Other income was realized from interest on investments and rentals from land that still remained in their own hands. The feuars could build on their feus and sell them if they wished and with the agreement of the society. Any new purchaser also owed feu duty to the society and sometimes 'entry money', a one-off charge. This steady income influenced the development of the society.

In 1832 the reforming zeal of a new secretary transformed the society once more. Sickness benefit and charitable donations were abolished, as was the quarterly subscription that had mostly sustained these payments. Instead, the society concentrated on providing annuities or pensions to members over the age of 65: the society's land wealth and admission rates served to cover outgoings.

The minute books and ledgers of the Society are held at Dunfermline Local Studies Library. They are remarkably complete. They can be used to follow the development of the society as a whole, both its changing role and its membership. They provide an insight into the development of a part of Dunfermline that was still open land when the society purchased it but which was fully developed when the society celebrated its 200th anniversary in 1916 by marching the boundaries of their property. And they throw light on the social history of families and individuals in Dunfermline.

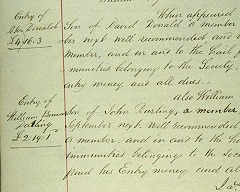

To single out just one member, Peter Donald was 38 when he joined the Society on 10 June 1864. Consequently, he paid high entry money - £4.16.3 (£4.81). Entry was charged at different scales for the first and subsequent sons or sons-in-law of members. Neutrals, those with no connection to the Society at all, paid even more. Entry money was also age dependant, reflecting the likely risk that older entrants would be on the society's outgoings. Tables indicating charges were published to keep members informed. Despite his age at entry, Peter Donald was able to benefit from his membership for many years. He was admitted as an annuitant (pensioner) of the Society on 31 October 1891 aged 65. At that time he was resident in New York. He died there on 9 April 1915 (aged 89). During this time his benefit totalled more than £150 - a good return on his investment.

Later members were not so fortunate. After the First World War and during the rest of the twentieth century inflation began to outstrip the growth in the sum that the society could distribute. By the 1980s, it was costing more to administer the Society's business than was paid out in annuities - £133.85 against £125. The remaining members expressed an interest in closing the society, which was first voiced at the annual general meeting of 1983. The next year the Clerk (a local solicitor) reported the opinion of the Registrar of Friendly Societies in Edinburgh that as 'the society owned the superiority of large subjects' there was 'no way of winding up'. As the value of annuities was further eroded, the society appears to have withered and died.

Free Gardeners Home | Diversity | Edinburgh