A Chill Reminder

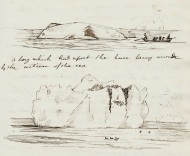

Among the reminders of a bygone trade are first hand accounts of voyages to the Arctic whaling grounds. These are recorded in journals and logbooks of members of the ships' crews. The manuscripts give details of the day-to-day routine of life aboard ship. They also give an indication of the excitement of catching the whale, known as the chase. Most of the accounts are written by young officers or ship's doctors. They sought out adventure at the ends of the earth rather than having to earn a living in one of the harshest climates in the world.

18th July 1903 is the date, there is a constant heavy drizzle falling on a barren rocky coastline. The ship, Diana, rises and falls gently in a modest swell, as it lies anchored to some pack ice. The silence is broken only by the occasional screech of a seabird and the sound of hammering. The ship's carpenter is hard at work, not with the necessary upkeep of the ship, but with the construction of a coffin. James Lamb, a young Dundee seaman, takes up the story:

One of the Harpooners named Edward Scott who had been lying badly for two or tree months died this morning at (6am). He suffered awfully.

[Journal of a voyage to Davis Straits. James Lamb.]

The following morning was bright and sunny and all hands were called to attend the funeral. Suddenly a cry from the masthead lookout indicated the presence of a whale. The coffin was immediately abandoned as the entire crew tumbled into the whaling boats and began the chase. The whale was eventually killed, brought alongside and flensed by mid-afternoon. Thoughts again turned to their dead colleague. Lamb continues with the narrative:

Davidson and boats crew were sent away to the land to dig a grave...After tea all hands were called on deck and the union jack was spread over the coffin. The captain read the funeral service from Corinthians...Then the boats were manned and the coffin was put into his own boat. All the boats' jacks (small flags raised at the stern of a boat to signal they had caught a whale) were half-masted and they all pulled in single file for the shore. The coffin was then placed on two oars and carried over the rocks to the grave side. The harpooners lowered him into the grave and then took the jack off and put the headstone up and covered the coffin up with earth and stone each man going and getting a stone for himself and putting it on. The chief then took a photograph of the grave with all hands standing round.

[Journal of a voyage to Davis Straits. James Lamb.]

Such were the hardships of life at sea. It could have been anywhere, a foreign port or a desert island, but even death in the Arctic had a peculiar poignancy. Buried in a frozen waste where digging even a shallow grave was not always possible was the fate of many an Arctic whaling seaman. Their headstones and memorials are still visible to this day. Other more tangible objects exist in family homes and on public display in museums all over the country. They are a chill reminder of days when oil came from the Arctic.