Today, 31 January 2019, marks the centenary of ‘Bloody Friday.’

One hundred years ago, a workers’ protest championing improvements to pay and working conditions and shorter working weeks descended into skirmishes with police in Glasgow’s main civic square.

The event, also known as the Battle of George Square, was part of a sustained period of left wing militant action in the West of Scotland. It has subsequently been known as ‘Red Clydeside’, and would last until the 1930s.

Here we explore some of the events and tensions that led to the riot.

A photograph of George Square by Thomas Annan of Glasgow (1829-1887)

‘Red Clydeside’: Left Wing Activism During WW1

During the First World War, Glasgow played a crucial role as Scotland’s industrial powerhouse. It provided the Navy with ships and submarines, and met the constant demand for munitions.

The city’s population quickly expanded during this time. Workers moved into the area from all over the country. This rapid expansion meant a huge working class population faced cramped living conditions.

These worsening conditions, coupled with growing unionisation among workers, contributed to a rise in socialist interest in the West of Scotland.

Many felt the Liberal government of the time did not represent the working class. Workers protested throughout the war years, striking in factories, mines and shipyards.

A photograph depicting a scene in George Square on ‘Bloody Friday’

The Clydeside Rent Strike and Munitions of War Act

At the same time, landlords increased rents despite housing shortages.

The Clydeside Rent Strike of 1915 saw organisations like the South Govan Housing Association (led by Mary Barbour and Helen Crawfurd) take action.

These strikes were backed by trade unions, the Labour Party, suffragettes and other left wing political groups.

The introduction of the Munitions of War Act in the same year added more discontentment.

The Act allowed lower skilled workers opportunities to perform work that would usually require someone with much higher skill. It allowed employers to increase working hours and cap wages.

Tensions between the government and Glasgow’s working class continued to grow throughout the war years, coming to a head soon after the Armistice.

Glasgow’s leading law officers survey events in George Square on ‘Bloody Friday’

Bloody Friday: The Battle of George Square

The conclusion of the First World War saw thousands of troops return to Britain, flooding job markets.

In Glasgow, the trade union-led Clyde Workers’ Committee (CWC) wanted to help create jobs for returning soldiers by reducing the average working week for those already in employment from 54 to 40 hours.

They called for a “40 hours strike” and went to Glasgow City Chambers to present their case to the Lord Provost on Wednesday 29 January 1919. They were supported by thousands of striking workers outside in George Square.

On Friday 31 January, tens of thousands of demonstrators gathered in George Square to hear the Lord Provost’s reply to the CWC’s requests.

CWC leader Davie Kirkwood lying on the ground after being batoned to the ground by police

What began as a protest soon became a riot. Clashes broke out between the police and the striking workers. Fighting across the city continued throughout the night. 53 people were recorded as injured.

Within a week of the riot, a compromise was met and the working week was reduced to 47 hours.

Red Clydeside Today

Our digital archive, SCRAN, holds a host of resources related to ‘Red Clydeside.’

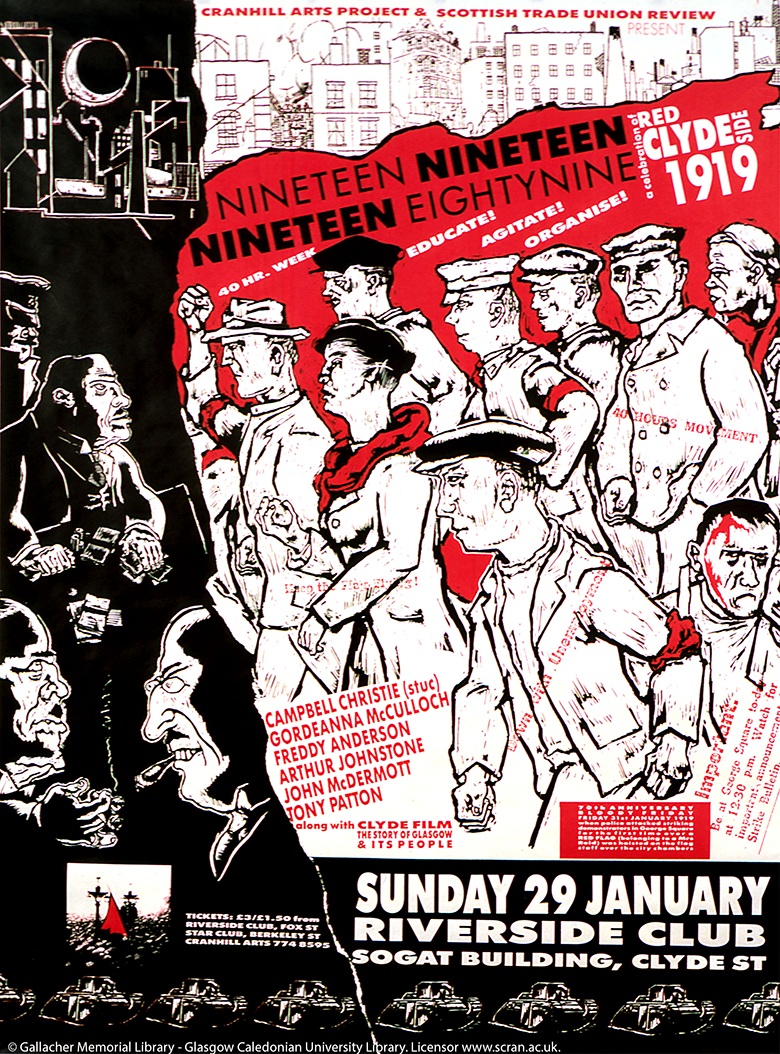

A poster commemorating the 70th anniversary of ‘Bloody Friday’

These resources can tell us a lot about the growing militancy of workers over this period, especially in the build-up to the Battle of George Square, as well as its aftermath.

However, they don’t tell us the whole story.

The sequence of events around ‘Bloody Friday’ have long been disputed, and further research is still ongoing into the build-up and aftermath.